Dear Future Reader,

There’s no version of this story that can be told in the present, for reasons you’ve likely heard about by now. Every age has its inconvenient narratives and, worse, stories that for whatever reason can’t or won’t ever be told. This is one. Though it’s a story that might feel familiar to you, as stories born from grief often do. I’m guessing you in the future know as much—but hopefully not more—about grief than us here stuck in the present of our own making. The source of our grief is, of course, a death. You’ve known similar suffering, no doubt, and understand as we do now that grief is a process.

But without acknowledgment, the process of grieving is stunted, and the grief becomes a haunting.

The first few people we told, before we realized we couldn’t really say anything to anyone, told us, Welcome to the other side. They knew the journey we were about to embark on, but didn’t know that present circumstances would lock us in sorrow, halting our progress through the stages we needed to travel.

We’re told the day will come when we’ll only have happy memories, which we’d love to believe, mired as we are in the recent narrative that led us to such an unhappy place:

The great upset that had us all sheltering in place as much as possible, avoidance of human contact our most important goal. The daily counts of lives lost drumming in the background for months and months, horror upon horror, our collective will bent as it had never been before.

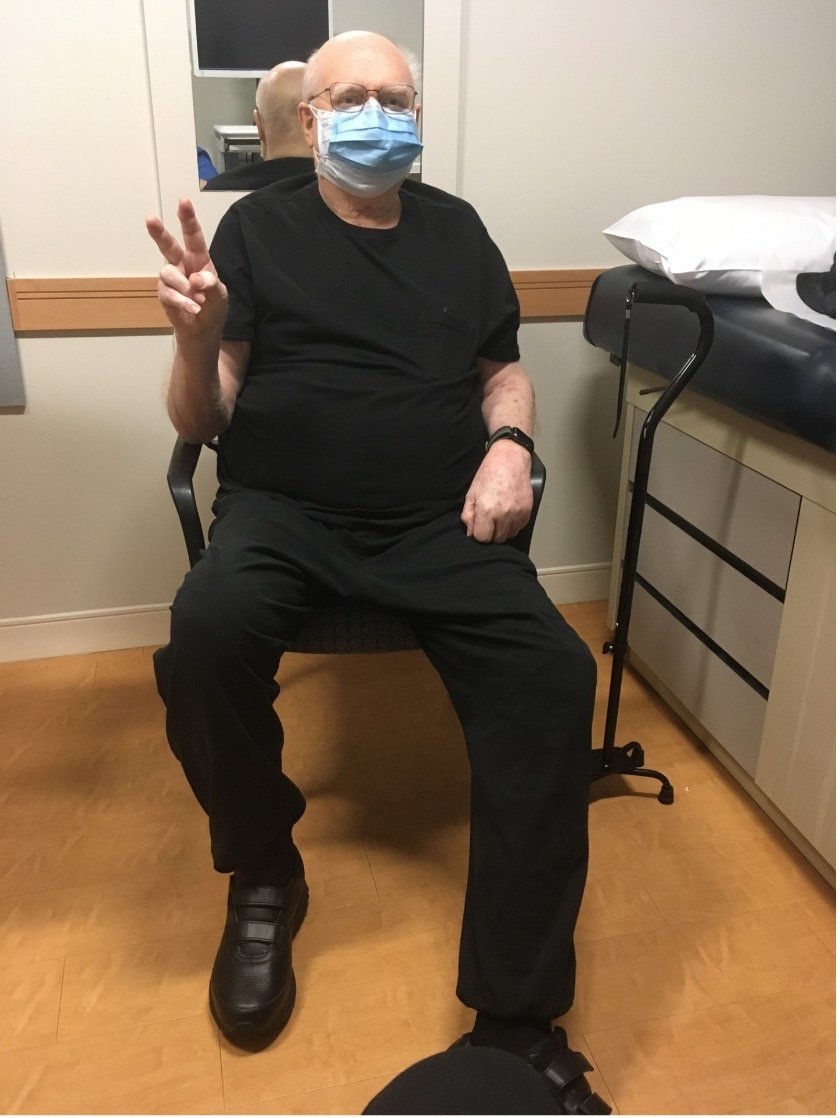

Then: news of freedom, a release from our new hated routines. The remedy is in short supply at first, and common sense dictates that the older population, which includes our father, and those who are among the hunted, will be given priority. The remedy must be administered twice, between intervals, and after the cycle is completed, my father was unable to move his arm and it hurt so badly he considered going to the emergency room. But the news was full of people saying that their arm hurt for a couple of days after, so he waited. The pain subsided some, even though his arm was still immobile. He was hopeful mobility would return. X-rays were taken, but showed nothing.

Late summer and into September, he started to have a cough that he

couldn’t shake. Mid-September, the cough was so bad that he couldn’t speak without coughing. He was fatigued all the time and was often dizzy. Soon he wasn’t able to leave home for his errands or to visit his grandson. He began using a cane to steady himself, and one night while taking out the garbage, he fell on the pavement and ended up in the ICU.

When he was admitted, doctors noticed that his sodium was low and that he was anemic, though they couldn’t figure out why. It would turn out later that he had low sodium generally, so any drop in sodium naturally led to problems. He spent a few days in the ICU, mostly because they didn’t have a hospital bed for him on the main floor.

He finally got a room on the cardiac wing. A series of blood tests were performed. Blood transfusions were administered using a blood warmer to combat the anemia. He spent almost a month in the cardiac unit as he was experiencing atrial fibrillation. Months later, his new cardiologist would toss out the nugget that half the population has undiagnosed atrial fibrillation.

One day an oncologist came to his bedside and did a bone marrow biopsy to look for signs of cancer, as well as hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, known as HLH, a condition whereby white blood cells aggressively attack red blood cells. But the biopsy turned up no signs of either. The oncologist asked the radiologist to look again, and the second time around they found “a tiny bit” of evidence of HLH in his bone marrow.

So the assumption became that a cancer was driving the HLH, and my father was transferred to the oncology wing. Tests were started in earnest to locate the cancer and determine its type, each coming back negative. But certain blood markers seemed to contradict the findings. At this point his hospital stay was entering its second month, and he developed a bedsore. Because so many tests were being run, he was sometimes on water restriction, and once when I was sitting with him, he faded out and alarm bells rang and I was kicked out of the room while the crash team brought him back to life.

I asked the oncologist if my brothers should fly out. “I know you’re not a travel agent,” I said sheepishly. The obvious question I was asking was: Is he going to make it or not? But I’d asked the oncologist to always be frank, and for the duration of our time with him, he appreciated being able to speak freely, often confessing how humbling practicing medicine is.

“I get that question all the time,” the oncologist admitted. “If they’re able to come, they should.”

And so my brothers rearranged their lives and flew across the country. My father was happy to see them, and we each took turns sitting with him during visiting hours, none of us having any clarity about what was happening, or would happen.

When the “tiny bit” of HLH evidence was discovered, the oncologist decided to go ahead with a treatment, assuming the cancer would come into focus, which we all agreed with. The first step was a high-dose steroid, but the steroid agitated my father, and he required so much attention from the nursing staff that he was transferred from the placid workings of the oncology wing to the more kinetic cardiology unit, against the oncologist’s wishes.

Before the agreed-upon treatment could start, it was determined that he’d been in the hospital so long that he was possibly too weak to withstand it. So a gentler chemotherapy treatment called etoposide was ordered. My father received two half doses before the oncologist decided he needed to be transferred to a medical rehab facility to build back his strength. He waited another week in the hospital for a bed to open up at the rehab facility. And, cruelly, the EMTs showed up in his doorway, ready to transport him to rehab, only to have the transfer called off because the rehab place couldn’t locate a blood warmer for transfusions, which my father required.

Once he finally made it to the rehab facility, most of his time on the chemotherapy wing was spent treating the bedsore and building back his strength. He couldn’t yet stand again and was confined to a wheelchair.

Desperate to spring him from rehab, my family and I agreed to the idea of discharging him to in-home physical therapy the moment he could stand on his own, which happened after about three weeks.

Desperate to spring him from rehab, my family and I agreed to the idea of discharging him to in-home physical therapy the moment he could stand on his own, which happened after about three weeks.

He was home with us for about two weeks or so, but we had to call 911 when he became fatigued and confused from low sodium and a too-rapid tapering off of the steroid he was on. He was in the hospital for about a week but wanted to be home for Christmas, and so he was given a blood transfusion and fluids on Christmas Eve and was able to come to our house again.

We worked on physical therapy daily, and he became an outpatient at the cancer center at the hospital.

His oncologist began tapering off the steroid more slowly, and my father had weekly visits to monitor his vitals. And to receive blood transfusions. He started and completed a two-month etoposide regimen, which seemed to work. But after about five weeks, his lab work tanked again.

His oncologist began tapering off the steroid more slowly, and my father had weekly visits to monitor his vitals. And to receive blood transfusions. He started and completed a two-month etoposide regimen, which seemed to work. But after about five weeks, his lab work tanked again.

At this point the oncologist said, “I hear the dog barking but just don’t see the dog,” meaning that he was sure a cancer he couldn’t see was driving the symptoms. We agreed to another round of chemo, or possibly a more aggressive chemotherapy. “Think of it as a phone conversation we’re trying to hang up on, but the other party won’t get off the line,” he said.

But then after another week of labs, he said, “I don’t hear the dog barking anymore.” And the chemotherapy was called off.

My father was admitted to the ER again shortly thereafter for weakness and fatigue and confusion. The blood markers that the oncologist had been watching were again all over the place.

At our next weekly visit, the oncologist presented us with a medical paper, which had yet to be peer-reviewed, about cases where the remedy had induced HLH. The author of the paper had identified about a hundred people who’d had the same reaction to the remedy that my father had, and it was interesting to read that many had survived, though some had unfortunately died. On its face, the survival rate for patients with HLH hovers between 30 and 50 percent, and the oncologist said from the beginning that my father had a one-in-two chance. The paper suggested that a rheumatoid arthritis drug had been successful in stopping the white blood cells from eating the red blood cells, so we decided to try the drug, even though we had to pay out of pocket for it, which the oncologist was not happy about. My father’s labs seemed stable for a period of time, but over the next few weeks, he still needed a blood transfusion or two.

Two trips to the ER via 911 followed, and then news came from the oncologist that a donor who had given the blood for one of my father’s transfusions had subsequently tested positive for blood parasites. The oncologist ordered a blood test, but no parasites were found.

Three weeks later my father took yet another trip to the ER, as he was complaining of abdominal pain and shortness of breath. The ER discharged him the next day.

A week later his labs showed his sodium to be low, and he was fatigued and weak and confused. He was admitted to the ER, given fluids and a blood transfusion, and discharged.

It was clear the rheumatoid arthritis drug was not working.

By mid-summer, there were more bad days than good. He became too weak to attend his weekly appointments with the oncologist, and in the days leading up to what would be his final appointment, he was bedridden and sleeping a lot. On a teleconference, the oncologist admitted, “Nothing we’re doing seems to be working.” The multiple conversations at my father’s weekly outpatient appointments, about how there were many treatments to be tried, failed to take into account how much the body could withstand. The oncologist decided to have my father transported to the hospital by ambulance, and after visiting with him, the doctor said it was clear the HLH had affected his brain.

My father was put on the comfort care floor while we searched for a hospice facility, and my brothers again arranged to fly out. I arrived the next day to find him on morphine, part of the comfort care protocol. He’d been agitated and anxious, but the morphine had done its job, and I sat next to his bed while he chatted away. Then something occurred to him and he started to cry—I’d never seen my father cry—and he said, “I just hope everyone gets what they want.” I said that all of us had everything we’d ever wanted and more, and his constant dedication and support for me and my brothers had been the difference in our lives. Then he said, “I always felt like I could’ve done more.” I told him that as a father now myself, I understood that feeling, guessing that all parents feel the same, but I told him, “Doesn’t mean it’s true.”

One afternoon while we were awaiting word on a hospice facility, he suddenly had a stroke. His face turned red and he started rocking violently, calling out for his grandfather, who had been his primary caregiver in his childhood. Because he was on comfort care, he wasn’t connected to anything, so I ran into the hall and yelled for help. A team scrambled into the room to find my father lying comatose in his hospital bed. They kept calling out his name, but nothing. They rushed him out of the room, and I was left standing in the corner, looking at the posters my wife and son had made, taped to the wall next to where the bed had been, wondering if that was it, but the care team wheeled him back some time later and his eyes lit up when he saw me. He seemed not to know what had just happened, assuming that he’d been taken away for yet another test.

One afternoon while we were awaiting word on a hospice facility, he suddenly had a stroke. His face turned red and he started rocking violently, calling out for his grandfather, who had been his primary caregiver in his childhood. Because he was on comfort care, he wasn’t connected to anything, so I ran into the hall and yelled for help. A team scrambled into the room to find my father lying comatose in his hospital bed. They kept calling out his name, but nothing. They rushed him out of the room, and I was left standing in the corner, looking at the posters my wife and son had made, taped to the wall next to where the bed had been, wondering if that was it, but the care team wheeled him back some time later and his eyes lit up when he saw me. He seemed not to know what had just happened, assuming that he’d been taken away for yet another test.

Over the next couple of days, we sat together in silence while various nurses who had administered to him during the past year stopped in to say hello. Many times, I would arrive at the hospital to find nurses who weren’t his in his room, chatting and laughing with him, attention that he loved. These miracle workers were always commenting on how sweet my father was to them. My father and I were constantly amazed by how stressed the healthcare system was, especially in fall 2021 to spring 2022, yet somehow the nursing staff found their humor and grace.

A hospice facility was finally located, and the nurse he knew best, who told me he reminded her of her own grandfather, was in the room when they came to transport him. At this point he thought he was just being transferred to a different room in the hospital, but she said goodbye to him. He waved, and she looked at me and pulled down her mask and stuck out her lower lip and frowned. I thanked her for everything and turned away before my emotions overtook me in the hall. I followed my father’s transport to the elevators, then drove the short distance to the hospice facility. By the time I arrived, he was settled in his room with panoramic views of woods and the nearby lake, a scene that would’ve reminded him of his childhood in Montana.

We passed the time mostly in silence. The steroid he’d been on had made him medically diabetic, and he could hardly see the Red Sox game on the TV. “I haven’t had a beer in forever,” he said, maybe remembering all the times we’d gone to Fenway Park and had many beers together. I remembered someone on the hospice staff telling me that it was okay to give patients alcohol if they asked for it. My brothers were due in that night, and I decided we’d bring some beer the next day for one last drink together.

But the phone woke me early the next morning, and a woman I didn’t know and would never meet called to say that our beloved father, a best friend as much as a parent, had passed away.

How our grief mimics everyone else’s: You’ll be going about your life, maybe executing a mundane task, one beaded on the chain that makes up your daily routine, and your breath will catch and you’re suddenly overwhelmed with loss.

How it doesn’t: when people ask about our father, we have to make a lightning decision about whether or not to tell the truth, which is a conversation stopper, or to offer a vague suggestion to spare the listener any uncomfortableness.

Sometimes, we let other peoples’ doubts become our doubts and feel relief at the notion that our grief is caused by something else, anything other than the secret we’re made to keep.

And we pay attention to other tragedies and have empathy with the grief of the survivors, ultimately envious that they’re on the path to healing.

But mostly, the loss feels enormous, and endless.

What we miss most:

--the unlimited kindness, which we’re guilty of having sometimes mistaken for weakness

--a curiosity about all that is unknown

--the benefit of the doubt

--and joy

We trust this finds you and yours in good stead. It sometimes feels in the present like hope is an artifact of the not-too-distant past, but those of us who tend to our reserves do so with the wish that it made a difference to you in the future. We’ll have to keep wishing it to be true and resist giving in to the prevailing sentiment that all is lost.

Vale.